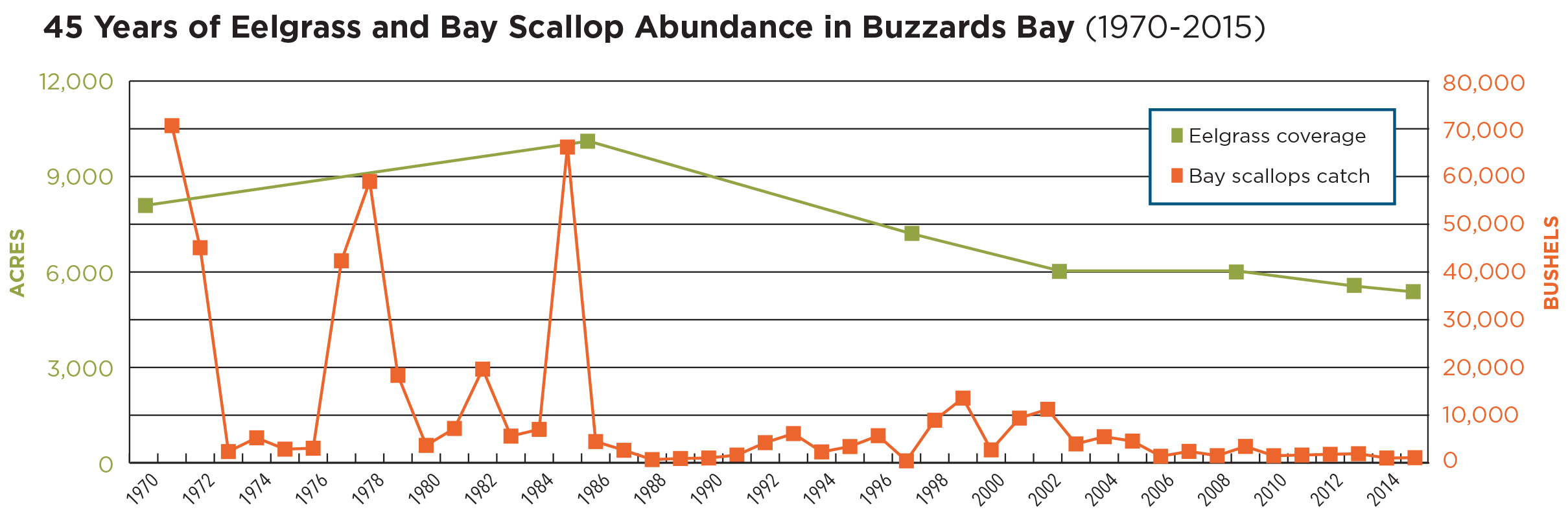

One graph shows the stunning collapse of bay scallop populations in Buzzards Bay

October marks the opening of the recreational bay scallop harvest season in Buzzards Bay. If you’ve never gone bay scalloping, you aren’t alone. There are so few bay scallops left in Buzzards Bay that hardly anyone is harvesting these shellfish at a reportable level anymore.

Bay scallops were once to Buzzards Bay what oysters were to the Chesapeake Bay and Long Island Sound: highly valuable and deeply connected to our culture. But today, our once-abundant bay scallops have all but disappeared.

This issue is highlighted in the new documentary The Last Bay Scallop?, which examines the declining Nantucket bay scallop fishery – the last commercially viable bay scallop fishery on the East Coast. The New Bedford Fishing Heritage Center will be co-hosting a screening of the documentary with the Coalition and the New Bedford Whaling National Historical Park on Friday, Oct. 21 as part of the Dock-U-Mentaries series.

Buzzards Bay’s bay scallop population has suffered an ecological collapse. In the 1970s and 80s, 70,000 bushels of bay scallops were harvested from the Bay. Forty years later, that amount has dropped to just 1,500 bushels. It’s a stunning decline – one that is linked in part to nitrogen pollution.

Bay scallops live among eelgrass beds, which grow underwater in shallow harbors, coves, and tidal rivers. Most small fish and shellfish rely on the shelter of eelgrass beds to hide from predators, but bay scallops depend on eelgrass for an additional role during reproduction. Unlike other shellfish, tiny juvenile bay scallops actually attach to eelgrass blades by thin threads, eventually dropping off when they grow large enough.

Eelgrass needs clear, clean water to grow. But nitrogen pollution fuels the growth of algae that makes the water cloudy and murky. If there isn’t enough sunlight reaching the bottom, eelgrass dies. And those species that depend on eelgrass – like bay scallops – begin to vanish, too.

During periods over the past 45 years when there was greater eelgrass acreage, bay scallop harvests peaked. But since the mid-1980s, nearly half of the Bay’s eelgrass beds have died off. As eelgrass meadows have disappeared, so have bay scallops.

This graph shows the relationship between these two independent, but closely related, indicators over the past 45 years. During periods when eelgrass acreage was higher, such as from 1970 to 1985, bay scallop harvests peaked. Since the mid-1980s, nearly half of the Bay’s eelgrass beds have died off. As eelgrass meadows have disappeared, so have bay scallops.

Unfortunately, the collapse of bay scallops is more complicated than just the health of our local waters. A similar story is playing out in waterways up and down the East Coast, from Florida to Rhode Island. Once-rich bay scallop areas like Narragansett Bay, Tampa Bay, and even Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket have seen their scallop populations dwindle in recent decades.

Using over 20 years of the Coalition’s Baywatchers data, scientists found that average summertime water temperatures in Buzzards Bay have risen by roughly 4 degrees Fahrenheit.

What’s more, Buzzards Bay’s water temperatures are increasing. Using over 20 years of Baywatchers data, scientists from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution found that summer water temperatures in Buzzards Bay have warmed by roughly 4 degrees Fahrenheit.

Warmer water is more vulnerable to the effects of nitrogen pollution. In many spots around the Bay, data show that nitrogen pollution has levelled off but the water isn’t any clearer. More algae is growing, even in places where nitrogen pollution isn’t increasing.

It’s clear that climate change is moving the goalpost for nitrogen reductions. To save Buzzards Bay and all its species – including bay scallops and eelgrass – we’re going to have to work harder than ever. But it can be done.

Bay scallops and eelgrass need one thing: clean water. The good news is that we may be at a turning point for nitrogen pollution in Buzzards Bay. In the latest State of Buzzards Bay report, we found that the score for nitrogen pollution did not get worse for the first time in over a decade – signaling an encouraging pause in nitrogen-related declines.

As work continues to reduce nitrogen pollution from septic systems and sewer plants, prevent new sources of pollution by conserving land, and even restore bay scallops in areas where they were once abundant, the Bay’s signature shellfish may begin to return to health.